This article was published in Play and Folklore no. 66, December 2016, by Museum Victoria.

In 2007 and 2008 I had the privilege of working for the Childhood, Tradition and Change project as a fieldworker. The project was funded by the Australian Research Council Linkage Project Scheme and received additional support from the National Library of Australia, Museum Victoria, Deakin University, Curtin University and the University of Melbourne. The research was conducted over four years (2007-10), and material was recorded in nineteen schools across Australia by eight fieldworkers working in pairs.

The aim of the project was to gain a ‘snapshot’ of play occurring in Australian playgrounds and to build on an extant body of work compiled by researchers in the 1950s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. (1)

Entering the field

Armed with pencils, notebooks, cameras, folders, microphones, a packed lunch and studio-quality recording gear (from the National Library of Australia), my colleagues and I set out to document what primary school kids were up to during their free play time: at recess, lunch, and as they headed home each day.

My first location was a public school in Melbourne’s outer-north (School X). This was part of the pilot project and an initial investigation, and although our work here was not to be included in the final report, we were establishing protocol and methodology for the main, nationwide study. Only 52% of the student body at School X were from English-speaking backgrounds, the remainder representing a further twenty-nine nationalities. We were fortunate that the headmaster at School X was enthusiastic about the project, as were the parents. We were able to address the school assembly on the Monday morning so that students, staff and parents knew exactly why we were there and what we were doing.

The second school I visited was a private ‘alternative’ school (School Y) in Melbourne’s inner-eastern suburbs, as part of the nationwide study. A much smaller school, most students were from English-speaking and higher socio-economic backgrounds. We weren’t able to address the whole school at School Y, though the community was equally as cooperative and welcoming. Other fieldworkers experienced very different reactions from schools, principals and parents; more on this later.

Mapping

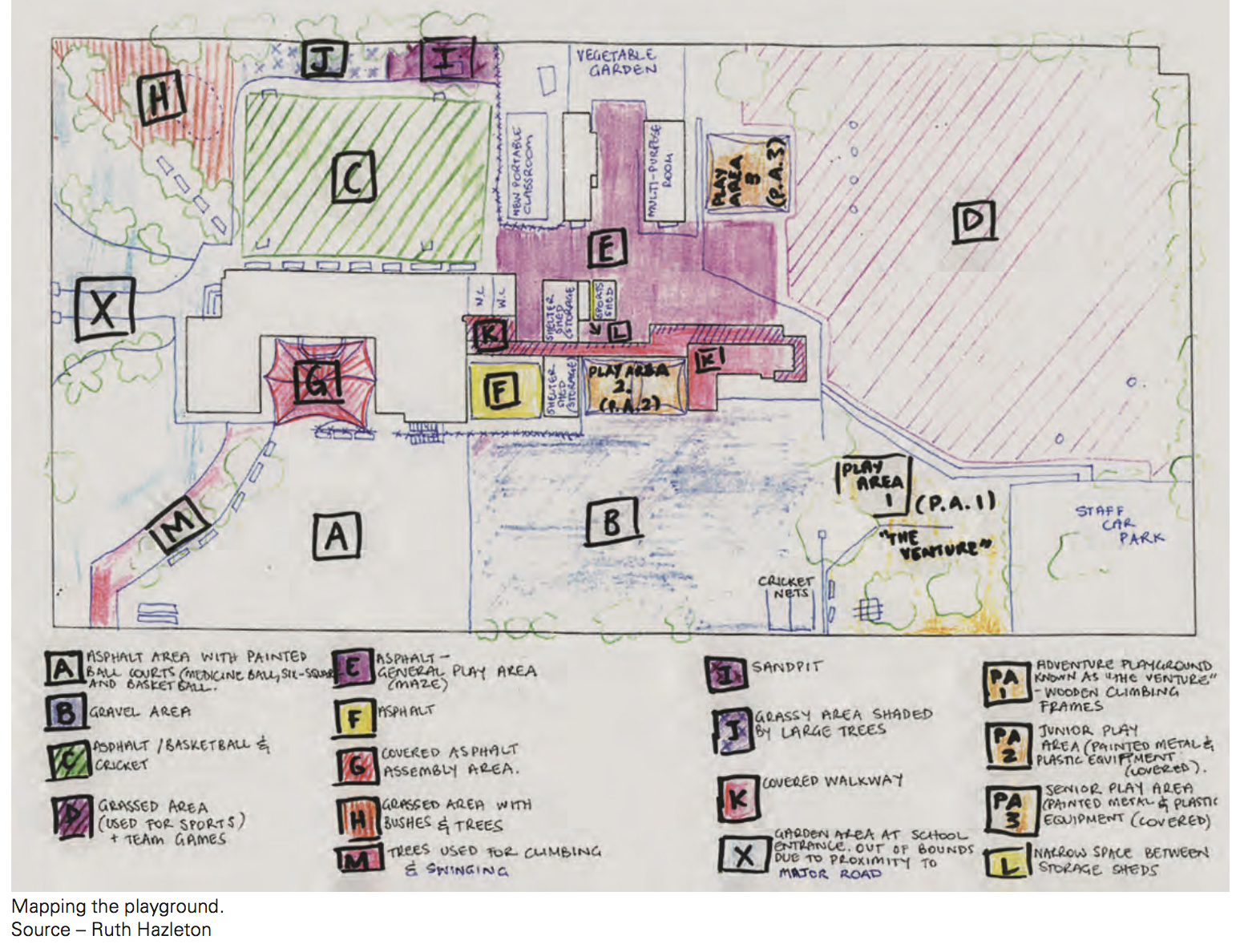

After finding our way around each school and seeking quiet areas where we could conduct interviews and work during class hours, we began to map playgrounds. Initially, this was done during class time without students present and later added to as we were able to identify which areas

of each school were significant in terms of the way the children played during recess and lunch times.

It sounds fairly simple, though there are a number

of layers of mapping that need to be documented. Apart from the obvious (mapping buildings and open spaces), we had to ascertain which play areas were open to different age groups, where were the ‘out- of-bounds’ areas, what, if any, play equipment was available to students and where it was kept.

After finding our way around each school and seeking quiet areas where we could conduct interviews and work during class hours, we began to map playgrounds. Initially, this was done during class time without students present and later added to as we were able to identify which areas

of each school were significant in terms of the way the children played during recess and lunch times.

It sounds fairly simple, though there are a number

of layers of mapping that need to be documented. Apart from the obvious (mapping buildings and open spaces), we had to ascertain which play areas were open to different age groups, where were the ‘out- of-bounds’ areas, what, if any, play equipment was available to students and where it was kept.

The second layer of mapping required us to document all play areas that had been in any way prescribed for certain activities, including designated sports areas and play equipment (basketball courts, football goals, monkey bars, climbing structures, sandpits, slides, etc.). Public schools also usually have areas where hopscotch games, alphabet snakes, ballgame markings and the like have been painted on the ground and walls – usually by well-meaning adults. If and how children interact with these is also an important observation to make when in the field, and for this reason, these were also included on the map.

Lastly were the play areas established by the children themselves, often the most significant areas in terms of observation. Teachers will sometimes be aware of these areas, though often they aren’t obvious to adults. Such areas might be centred around a collection of bushes or trees, a single tree, an alleyway in-between buildings, a patch of dirt where a hole is being dug, or a rocky outcrop along the school boundary. Sometimes it’s simply a place where children are least likely to be interrupted by teachers.

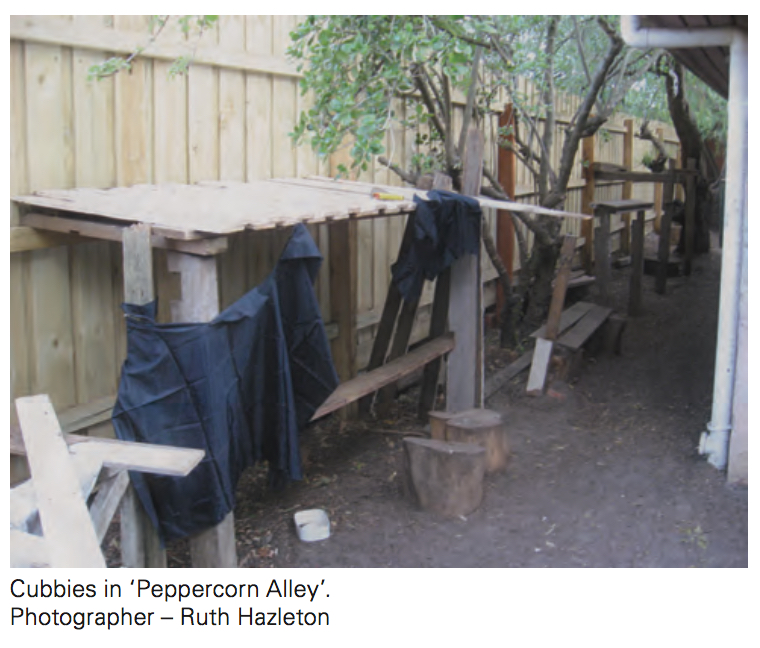

At School X, for example, we found a tree that was referred to by the children as the ‘abarmanation tree’ (‘abomination’ said with an American accent), and the adventure playground was always referred to as ‘The Venture’. At School Y, there were a number of places named by the children: ‘The Pines’ was an enclosed area separated from the surrounding grounds by a large sliding gate. This is where children would play ‘Gang Up’, as the gate served as a means to ‘trap people’. At the same school, children had tools available to them to build their own cubby houses. One of these rows of cubbies was referred to as ‘Hut Alley’, and a second row was called ‘Peppercorn Court’ and ‘Peppercorn Alley’.

In addition to creating the map itself, we photographed all the areas we identified on the map, labelling each area so we could easily record in which area play was occurring.

Celebrity, ‘tradition bearers’ and ‘adulteration’.

Celebrity, ‘tradition bearers’ and ‘adulteration’.

With a week to spend at each school, we began by wandering around separately, taking note of weather conditions, what the children were doing, where they were playing, how many of them were engaged in each activity, their gender and age. In those first few days we concentrated on general observations: firstly, to get a feel for the general play environment, and secondly, to document which children were the ‘tradition bearers’ we’d like to interview and/or record later in the week. A ‘tradition bearer’ is a term folklorists use to identify individuals who display the most knowledge of games, rhymes, rules, etc.

At the beginning of each week (particularly at School X), our presence in the playground was far from inconspicuous – we were like school-yard celebrities. The second we pulled out a camera or video camera in the playground, kids would follow as though we were the Pied Piper. This was problematic in that children would also gleefully make things up on the spot, exaggerate what they were doing and compete for attention. After a few days, however, the novelty wore off and they lost interest in us, which was when the best quality material started to emerge. In many ways, it was also very important that this ‘meeting’ process occur, as we needed the children to get to know us before they would open up and share their secrets.

As we worked, we would sometimes intervene and ask questions about the rules if we needed clarification, ask them to repeat a rhyme or describe the game they were playing in their own words.

Ideally, play is best observed without intervention, and this is a primary difficulty confronted by fieldworkers. By intervening, the researcher will interrupt the ‘play flow’ and break the spontaneity of the moment, which results in what professional playworkers aptly refer to as ‘adulteration’. The researcher balances on a fine line between ‘observer’ and ‘participant observer’. By becoming involved we could easily influence the direction in which the play was heading, or even bring play to a halt. This could result in missing an important event or, at worst, being avoided for the rest of the week as a ‘play-destroyer’. Generally, however, most kids will happily pick up where they left off or let their play evolve after an intervention.

Hoarding treasure: categories of play and school rules

Across the entire Childhood, Tradition and Change project, over thirty-eight categories of play were recorded, including rhymes, clapping games, chasing games, ball games, quiet play, finger games, forbidden games, language play, counting play, imagination play, jumping games, role-playing, building and skipping games. (2)

My first encounter at School Y is one I’ll never forget. Within minutes of entering the playground, I observed a group of five and six-year-olds crouched underneath a demountable building. They were each equipped with a hammer and a pair of swimming goggles, totally absorbed in the activity of smashing rocks. As mentioned previously, School Y can be described as ‘alternative’. Very few school rules dictated how children played, tree climbing was encouraged as was the use of tools, hammers and nails, and play was largely self-directed.

School X had more formal rules in place, though the culture there still valued ‘free play’ over structured play during recess and lunch hours. Because of the freedoms inherent at both schools, the material we were able to collect overall was rich and varied. The basic rule of a fieldworker is to never presume that the children are not engaged with something!

At both schools, traditional verbal lore such as the clapping rhymes ‘Cinderella Dressed in Yella’, ‘My Boyfriend Gave Me an Apple’ and ‘Miss Mary Mack’ were still prevalent, as were the endless variations of ‘Tiggy’ ‘Chasey’ or ‘Tip’. The most commonly documented forms of play were miscellaneous physical play and activities, alongside imaginative play often inspired by characters from popular culture, video games, television and film.

In comparison to Schools X and Y, fieldworkers at a number of different locations throughout the project reported very different experiences. At one school, the Principal was very suspicious of the activities of researchers, and had introduced a great many enforceable rules that ultimately dominated playground culture. At another school, one of the staff noted that it was the Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) Officer who determined playground culture where an abundance of school rules had been adopted in the name of ‘safety’.

Some of the rules noted at these more play-controlled schools included no scratching in the dirt with sticks (as soil would wash away in the rain), no poking sticks in holes in the trees, no cartwheels, no piggy-backing and no ‘Chasey’, ‘Tip’ or ‘Tiggy’ to be played on climbing equipment. Often such rules were not formalised in writing but put in place verbally by senior members of staff or OH&S representatives.

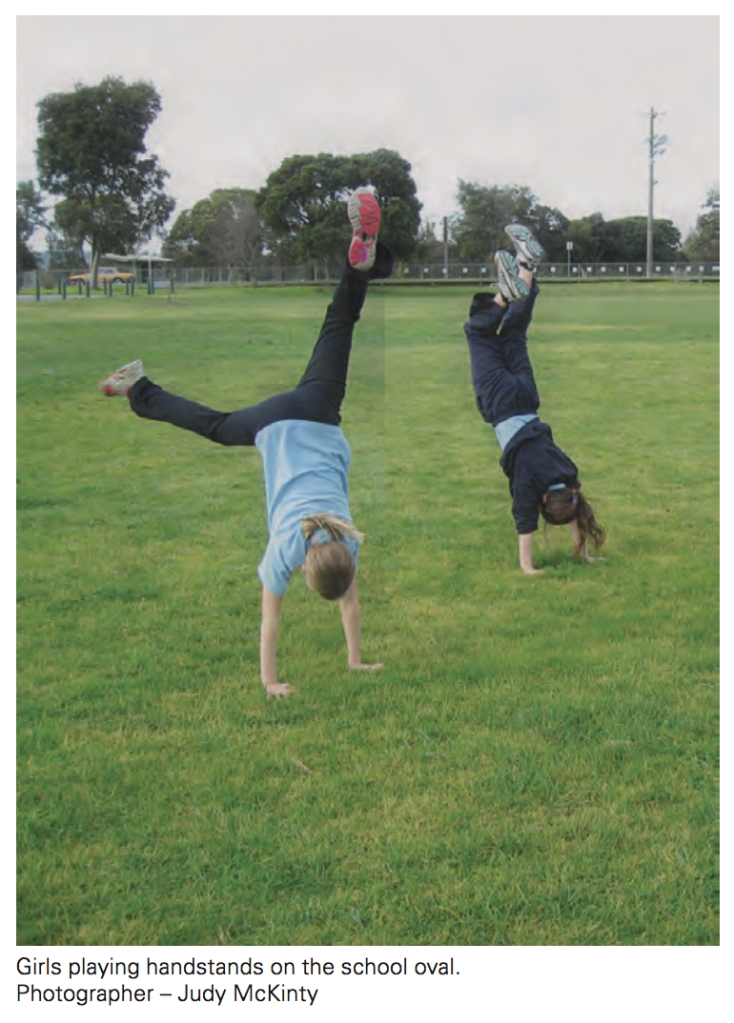

When asked about the effect a heavily regulated playground has on play culture, fieldworker Judy McKinty observed that children still played, but would engage in more subversive play to get around the rules. Children were observed tailoring their play to suit the attitudes of individual teachers on yard duty, would play a forbidden game when teachers weren’t looking, and would even re-name a forbidden game so they could continue playing. In one instance, girls who were not allowed to do cartwheels created a game called ‘I Am the Greatest’, which involved doing handstands, edging as closely as they could to doing cartwheels.

Children are incredibly adaptive and innovative in

the face of regulation, though overall most schools reported a fairly easy-going attitude to playground rules and regulations. As stated in the official report:

Children are incredibly adaptive and innovative in

the face of regulation, though overall most schools reported a fairly easy-going attitude to playground rules and regulations. As stated in the official report:

The spread of nineteen schools visited reflects a broad range of playground contexts and experiences; from wealthy non-government schools to government schools in extremely socio-economically disadvantaged areas; from schools in the tropics in summer to those in Tasmania in winter; from those with a playground dominated by natural bushland to those with little more than an asphalt quadrangle; from those where children are allowed to climb trees and use tools to build cubby houses to those where the flying fox on the playground equipment is chained up and no more than five children can play together as a group. In all contexts, children played games of their own choosing, and despite the differences, there were remarkable similarities across contexts as well. (3)

Also noted in the report were the words of one child who, after being banned from playing ‘Chasey’ for a week as a punishment declared that ‘Being banned from Chasey was like being banned from food, or TV’, illustrating how important such play is to a child and also perhaps what drives children to incorporate subversion into their play. (4)

Documentation and ethics

The methodology we used for collecting material differed slightly at Schools X and Y, though overall all games were initially documented by hand. Part of this documentation included noting who primary ‘tradition bearers’ were so we could then ascertain whether or not we could record them using a camera, video camera and/or sound recordings.

Without questioning the obvious importance of ethics around studies involving children, ethics standards do make an enormous difference to the quality of research in this area and the ease in which play can be documented. During the pilot project (School X), and with the cooperation of the school, we were able to photograph and lm at will. Unless a parent had specifically objected to their child being recorded, and no parents had done so, we were able to document freely.

When the project began officially (School Y), a different ethical practice had been put in place, meaning that we were significantly limited in regard to what we could photograph or film in the playground, as each child was required to have written parental permission to be recorded. In some cases, we were able to photograph hands, feet and objects that were non-identifiable during play. Inevitably, however, we had to avoid recording group play as it would require collecting all names (thus intervening during play) and checking all children against permissions (time-consuming and not an ideal use of budget). In smaller schools, this might have been an easier task, but at larger schools, it was very difficult to navigate.

Due to the above considerations, we relied heavily on written descriptions and sound recordings. The former wasn’t so difficult but the latter presented a number of problems. Sound recording is an art form in itself. Heavy rain, noisy birds, traffic, microphone placement, sound quality and using unfamiliar equipment are all potential enemies. Trained by staff at the National Library, we’d been taught how to use the equipment provided to us. Working in pairs meant that one person could operate the equipment and document items that were being collected while the other conducted the interview.

While the content we recorded was of good quality, again the artificial process of interviewing children in a room setting took the activity (rhymes, jokes, clapping games, etc.) out of the playground context. In this situation children often became shy, distracted, would forget things and giggled a lot. Necessary perhaps, but not ideal.

Conclusions and musings

Conclusions and musings

At the end of each week, we were required to compile, edit and categorise photographs, films and written descriptions of all the activities recorded at each school; a time-consuming task, but one that gave us the opportunity to reflect on what we had found and observed.

Recordings and photographs from the project are being held at The National Library of Australia and Museum Victoria. Nearly 400 records of play were collected and many are available publicly on the Childhood, Tradition and Change website, (5) which will hopefully be accessed by researchers and public for years to come.

It’s been many years since I immersed myself completely in the world of the playground, though I’ve discovered that once you’ve engaged in children’s culture in such depth, you become a permanent observer. Since the project began I’ve also become a parent, and my involvement in this project has greatly influenced how I approach play and my understanding of how very important projects like these are in documenting children’s culture: a world where adults are rarely privy to the games, methods, ideas and influences that dominate self-directed play.

Ruth Hazleton has a Graduate Diploma in Australian Folklife Studies and is a folk musician, singer and folklore advocate.

ENDNOTES

1. Kate Darian-Smith & Nikki Henningham, Final Report of the Childhood, Tradition and Change Project, 2001, p.4. http://ctac. esrc.unimelb.edu.au/objects/project-pubs/FinalReport.pdf

2. ibid., p.14.

3. ibid., p.10

4. ibid., p.16.

5. University of Melbourne, Childhood, Tradition and Change Public Database: Home http://ctac.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/

Black & White photographs taken from Museum Victoria Collections (open access).

Leave a comment